Life doesn't end. It merely changes form.

I've never been a fan of what I call the "Bleak School of Literary Book Writing." In my many-times rejected and ignored short story "Metamorphosis or How to Become a Famous Writer or How to Make it Okay to Eat Unlimited Quantities of Candy Corn," the first-person protagonist (a struggling writer) defines this genre as fiction that "ascribes to the philosophy that life sucks, there is no way out, and this is best expressed through endless lists of obscure adjectives, designed to inject just enough intellect and depth to appeal to serious reviewers and get those oh-so-important front-cover praise blurbs."

I've recently read two books in a row that do not fit into this School because they are, in the case of the classic A Meaningful Life by L. J. Davis, filled with humor, or in the case of The Mustache by Emmanuel Carrère, decidedly not bleak because of the high-energy Kafka-esque plot turns. However, both of their endings seem to ascribe to the Bleak School's notion that if you can't get what you want, if you can't control life, if you can't even agree on a common reality, life is not worth living or else it is merely a bleak and hopeless exercise to tolerate.

In a no-longer available blog about Herman Melville's novella Bartleby, the Scrivener, I made the point that I don't believe Bartleby, a man who simply refuses to participate in life, is a victim of his oppressive obligation to make money unhappily, but rather he is walking apathy—a choice. Yes, he has an apparently loveless, joyless, purposeless life, in which (as in the earlier-referenced books) he cannot get what he wants and his death seems to be an attempt to at least control that. But I posit that all these conclusions are a kind of delusion and misunderstanding of what life is and what it is for. And therefore they are, in a sense, false endings. Read More

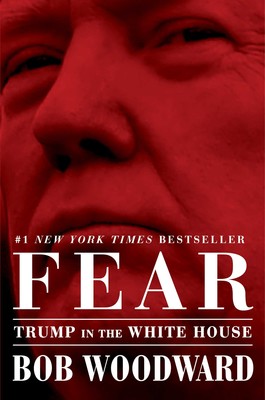

About a quarter of the way through this comprehensive history of everything leading up to the election of Trump and all the current events, Gary Cohn, the former president of Goldman Sachs who is the president's top economic advisor, attempts to explain our economy to Trump. He brings him copious research and data and finally makes it as simple as possible by asking: which would you choose—to go into a mine and get black lung or to make the same salary doing something else? He is attempting to intrude into Trump's belief that our trade agreements are disgraceful because we're losing manufacturing jobs—despite the data that more than 80 percent of our jobs are not in manufacturing and that a trade deficit is not a bad thing since it allows people to spend more money on what they're spending it on anyway—services. Nothing seems to penetrate.

About a quarter of the way through this comprehensive history of everything leading up to the election of Trump and all the current events, Gary Cohn, the former president of Goldman Sachs who is the president's top economic advisor, attempts to explain our economy to Trump. He brings him copious research and data and finally makes it as simple as possible by asking: which would you choose—to go into a mine and get black lung or to make the same salary doing something else? He is attempting to intrude into Trump's belief that our trade agreements are disgraceful because we're losing manufacturing jobs—despite the data that more than 80 percent of our jobs are not in manufacturing and that a trade deficit is not a bad thing since it allows people to spend more money on what they're spending it on anyway—services. Nothing seems to penetrate.

James Comey is a very good writer, storyteller, and teacher, so on a literary level (except for one odd plot order choice—the highly dramatic John Ashcroft hospital showdown between Comey and Bush representatives—which I suspect has to do with the need to insert a ton of detailed background information), this book works.

James Comey is a very good writer, storyteller, and teacher, so on a literary level (except for one odd plot order choice—the highly dramatic John Ashcroft hospital showdown between Comey and Bush representatives—which I suspect has to do with the need to insert a ton of detailed background information), this book works.