Click image to go to Substack Homepage.

Notes from a Crusty Seeker

For more frequent--and political--posts, subscribe to my free Substack columns; see "Quicklinks" section at end of righthand column.

Two Honorable Men: Adam Kinzinger & Steve Pink

This is an example of the material I'm publishing, sometimes daily, on Substack (free). To subscribe and have columns delivered to your email, go to : https://betsyrobinson.substack.com/

Why would I, a liberal progressive who watched every second of the January 6, 2021, hearings about the attack on the Capitol, want to watch and review a documentary film about Adam Kinzinger, the former Republican Congressman from Illinois who bucked his party and was a member of the Select Committee to investigate what happened?

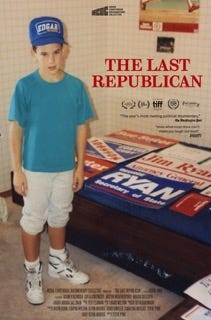

One might ask a similar question about filmmaker of The Last Republican, Steve Pink, an avowed "leftie" who Kinzinger knew from his film Hot Tub Time Machine (which I have not seen)—why would he want to devote a year of his life to making this movie?

The answer to both questions is LOVE—for love of honorable people. Kinzinger and Pink both reveal themselves to be that—Pink most often from the sidelines asking Kinzinger questions—and their affection for one another, within a mutual language of humor, is palpable.

Pink's 85-minute documentary, The Last Republican, pulses with truth and mutual respect, and therefore more powerfully conveys the history of what happened after the January 6th attempted coup as well as the reality that when two people with radically opposed beliefs come together with a common ground of truth, there can be love.

The Last Republican, which I saw at NYC's Film Forum in January 2025, opens with Kinzinger needling Pink about their opposing beliefs, but it quickly gets serious. We follow the history of the violent attack on the Capitol to attempt to overthrow the certification of the election, to what has become known as The Big Lie—Trump's continued claim that the election was rigged—to a recap of testimony. Even though I was glued to the entire run of the hearings, I was moved anew at the Capitol Police officers' recounts of "tragedy and sadness and defeat," which so gutted Kinzinger's pregnant wife Sofia, that she texted him from home: "Remind them that they won." … Which Kinzinger did, with gratitude and tears that ripped my heart open and, I wager, touched everybody in the Film Forum audience.

And the fact that the documentary cuts from this to Newsmax and Fox News's Tucker Carlson mocking Kinzinger's vulnerability evoked an audible gasp. It was not merely jarring; it was like seeing an ignoramus making fun of the nakedness of Michelangelo's David.* I felt so sorry for Carlson's inability to see what we were seeing: a completely open-hearted man whose every action is to help.

The film follows Kinzinger's decision not to run again after his district is redrawn to make a win impossible; we are generously invited into his life, his parents' life, and the arrival of his new son. We sit with him as the Republican Party votes to censure him, kicking him out of the party; as he recounts losing all his friends; and as the threats explode, requiring 24-hour security. And he becomes more and more lovable—not just to us but to the people around him: his home security team becomes invested in his baby's sleep training. His parents, who have a similar humor to Adam's, disparage family who insist on voicing their dislike to Adam's mom. But what never changes is Kinzinger's calm knowing that he did the right thing because there was a line he could not cross.

We learn the history of this from his childhood, to risking his life in Milwaukee for a stranger who was being attacked and bleeding out in a parking lot. At the time, Kinzinger was fresh from Air Force training (he joined following 9/11). Once we experience this incident in Kinzinger's raw retelling, we understand this man deeply. And love him more.

"Any courage I show comes from I just want to be able to look myself in the mirror," he answered when asked about the anomaly of his actions after January 6th. "I really don't think what I did is so courageous. It's just that I'm surrounded by cowards."

Steve Pink reminds him about the Milwaukee attack: "That was courageous."

Kinzinger first says it was stupid because you should never get in a fight with a person with a knife. But after reflection, "When you make the decision to give your life up for a stranger …[he pauses, tearing up]…I mean how can't that change you?"

When Pink asks about the next part of his life, Kinzinger says he will be in a fight against cynicism. "I don't want in the second half of my life to not be willing to put my life on the line for people."

Pink: "Even MAGA people?"

Kinzinger: "Yeah, even MAGA people. Maybe especially them because they need some inspiration that they're not getting. They're being lied to and abused."

As the film ends, Pink and Kinzinger embrace like bros. And as they walk off screen:

Pink: "If this documentary helps you win the presidency and you enact horrible conservative policies, I swear to fucking god—

Kinzinger: "Oh, I'll call my first horrible policy the Steve Pink Conservative Future Bill."

What Is an Honorable Person?

In a review/essay of First Principles: What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How that Shaped the Country, by historian Thomas E. Ricks, writer Richard Werber writes:

Merriam-Webster defines honorable as "deserving of respect or high regard" or "of great renown." "Honorable" is something earned from past behavior. But for the Founders, it was specific to judging behavior in the moment. And its meaning was clear. It was more than being honest. To be honorable, to make honorable decisions, was to consider and act as much, or more, for the welfare and happiness of others as for oneself.

The Last Republican is a stirring and affirmative (about our ability to get along with our disagreements) portrait of two honorable men: Adam Kinzinger and filmmaker Steve Pink.

_____________________________

* Interestingly, Michelangelo's David represented, not only great male beauty, but the defense of civil liberties embodied in the 1494 constitution of the Republic of Florence, a city-state under siege.

_____________________________

To join Adam Kinzinger's nonpartisan group in actions to save our democracy, go to Country First, with 300,000 active members, and counting.

Per Country First's action emails:

Our Days of Action have empowered nearly 9,000 volunteers, because they are a time designed to equip and empower you for action. Days of Action are meant to help you answer the question, "how do I make a difference?" And it's going to show you that taking effective action is easier than you might think.

The Last Republican is now streaming:

Google Play: Click here

YouTube TV: click here

ITunes/Apple TV: Click Here

Amazon: Click Here

In the meantime, enjoy the trailer:

Review: Dave Barry's Class Clown: The Memoirs of a Professional Wiseass—How I Went 77 Years without Growing Up

Full disclosure: I believe I am semi-intimately related to Mr. Dave Barry even though we've never met or enjoyed carnal knowledge. At only 9% into an advance e-copy of Class Clown: The Memoirs of a Professional Wiseass—How I Went 77 Years without Growing Up (pub. date, May 13, 2025), I was so delighted, entertained, and aroused that I prematurely ejaculated on Facebook:

Dave grew up in the 1950s in Armonk … just a hop, skip and a jump from where I was growing up in Briarcliff Manor.

His parents were married the same date as mine were. They were both smart and funny like mine. His father became an alcoholic but recovered. Mine didn't. And on and on and on.

I don't know whether to be jealous or in awe that I'm seeing a kind of parallel life in an alternate reality if only my family had been sane, nonviolent, and Presbyterian.

But it turns out that's where our parallel existences diverged.

Although Barry claimed to have been aimless after leaving college, flitting from bookkeeping to a local paper to misery at the Associated Press to teaching writing to business people, from my point of view as a writer who's slogged through publishing mud for more than 40 years, he was a goddam bird dog—zeroing in on Gene Weingarten (another writer who makes me guffaw) at the Miami Herald's Sunday magazine, Tropic … which is where this book became my personal hilarious writer's tutorial.

Lessons from Dave Barry: To do a successful humor column, it is critical to care nothing about the truth of your subject, what your subject is, or basically anything. Sometimes the stupider the questions, the more entertaining the column. Hence, my imagined interview with Dave Barry about his new memoir:

BETSY: Why class clown? For goodness sake, you were only in school for 12 of your 77 years (well maybe 16 if you count college, but by then you seemed to have outgrown clowning for clowning's sake). So isn't it kind of disingenuous to qualify your life by 1/6.416666666 of its duration? Speaking of which, what do you think of clowns? In my experience, they are often sad and depressed and they make lousy dates.

DAVE: Aw gee, I never dated a clown, Betsy. I'm sorry you had such traumatic experiences. We only picked that title because everybody in the focus group voted for the cover with six-year-old me in a party hat. I do look pretty cute, despite the buzz cut my father insisted on giving me, but he was probably drunk when he did it, or in the middle of writing a sermon—did you like the parts about my dad?

BETSY: Very much, Dave. Your dad seems like a swell guy, the way he helped so many people and took you, with his camp group, to the march in Washington, DC, to hear Martin Luther King, Jr. speak. (BTW, nice historical significance, giving the memoir the obligatory gravitas required for a Pulitzer. Smart move.*) Speaking of which, you said you didn't realize at the time that you were witnessing history. What were you doing standing there in the crowd in front of the Lincoln Memorial?

DAVE: To be honest, Betsy, my mom had insisted I wear laced shoes, and one of the staffers in my Camp Sharparoon inner city kids group thought it'd be a great joke to tie them together. So I spent a lot of the speech trying not to faint from the heat or fall down because we were packed so tight I couldn't bend over to untie them. But I've heard the speech on video many times—thank goodness for YouTube—and, like I said, it's mind-expanding.

BETSY: Speaking of almost dying, (I know we weren't but you seem okay with leaps of nonlogic), one of my favorite of your millions of quoted parts in the book (Great recycling! More leisure time to practice your broom and lawnmower marching skills and think about what to eat for dinner!) was your interview with Bob Graham, the then governor of Florida. And speaking of almost drowning in a harmonica accident (readers, you'll have to buy and maybe read the book to understand that—You're welcome, Dave!), have you ever played harmonica? I know you spent and spend a lot of time in a band—currently with a lot of famous writers—but how do you feel about blowing into a small box?

DAVE: Wow, what a creative question. Well, honestly, Betsy, I long ago stopped blowing into anything because it makes me hyperventilate, and particularly if I were to do so while standing next to a pool. I really valued Bob Graham's warning and establishment of the Harmonica Safety Day (Read the book!). Who knows how many lives besides mine have been spared. Full disclosure: I still do have impulses to blow into small containers, particularly if they make funny noises.

BETSY: What's a mutilated verb? I've heard of mutilated body parts and your description of your colonoscopy made me laugh so hard I may have fractured one of mine. But until your book, I never heard of "mutilated verbs."

DAVE: Wow, you're a real word person, aren't you? Try this:

It is my conclusion that the explosion in your head at the mention of this mutilation is due to the failure of the relief valve in your ears and may in the future result in sentences that are just too long for their own good.

See what I did? Lots of verb ideas have been mutilated into nouns: "conclusion," "explosion," "failure" and maybe some other ones that you added to this totally unauthorized revision of my book. Thus you pressed some really dull verbs into service. An unmutilated way to write it is:

"I conclude that your head exploded because your ears are blocked."

BETSY: Okay … So how about farts? You talk a lot about body emissions. Any final toots?

DAVE: Speaking of "toots," how come they don't rhyme with "foots" which brings me to footnotes. Did you like them?

BETSY: About footnotes**

_____________

*I'm not being cheeky. Dave has a whole section where he makes fun of newspaper writers' obsession with winning Pulitzers, so this sentence is a bit of an homage. BTW, Dave did win a Pulitzer—I'm not making that up—so I'm sure he won't take offense if he ends up reading this after all his book tour interviews, signing autographs, and setting fire to many pairs of perfectly good underpants (Read the book!).

**There are lots of footnotes in this book and, in the digital edition, the way they pop up when you tap the footnote number makes the jokes on top of jokes even funnier. Way to go, Dave!

_____________

DAVE: Thanks, Betsy.

BETSY: My pleasure, Dave. And thanks for the free book in exchange for an honest review … which I guess this really isn't. Whoops. Well, thanks anyway, and I'll think of you whenever I have nothing else to think about.

In Winter I Get Up at Night by Jane Urquhart

Here is my Goodreads review of Jane Urquhart's magnificent novel In Winter I Get Up at Night. Urquhart, a multi-award-winning celebrated Canadian writer, appears to be so obscure in the USA that the massive New York Public Library doesn't have this book. (Hence, the displayed e-book, courtesy of Bookshop.org. Same price as the amazonian's e-book.)

I don't say much in the review because I don't want to spoil any of the discovery of it. But there is a lot I'd like to say.

This is a book about seduction as it relates to racism. I would never say that in a review because it is completely at odds with what most people will feel for the longest time and maybe even at the end, they will not articulate it. But this is my post, so I'm saying it.

"For seduction is a soft thing," Urquhart writes near the end of the story. "It fills your rooms with golden light, sings your praises, makes you feel elected. Sainted."

In my opinion, seduction, not hate, is at the root of racism. People who practice allegiance to charismatic racists feel bathed in their "golden light." People who pick up modern slurs, denigrating others, are pumped up by superiority and righteousness so impermeable that, even when it is pointed out, they are immune to the notion that they are doing anything hurtful or wrong. People who feel a "manifest destiny" aka "entitlement" to privileges that are denied others have been drugged with a false sense of supremacy. They have been seduced and don't even know they are flying on ego as flimsy as a cloud.

But, writes Urquhart in the next paragraph:

"Abandonment, however, is not to be endured, because it provides proof that—no matter how he made you feel when he was now and then in town—you are ordinary after all."

Seduction based on the ego's need for superiority is always followed by abandonment.

Still Life and Remorse by Maira Kalman

Maira Kalman is brilliant!

This book reads like stand-up comedy for philosophical masses. The stories are snippets: commentary sometimes, sometimes personal stories. And they're delivered with a stand-up's or a performance artist's timing and pithiness, paired with paintings that demand to be looked at alone in a second paging through.

The still lifes are both paintings and moments within stories that manage, in so few words, to make you feel the insanity-causing dichotomies of love and remorse, love and rage, generosity and greediness, and every other opposite that we all contain. All this crazy turmoil of emotions is life. Or as Kalman writes: "the seething savagery / of our mundane lives." (81, slash connotes line breaks, as in poetry)

Maira Kalman is part gleeful sprite and part ancient wise woman. A true original who's found her niche—despite my comments about stand-up comedy and performance artists, this work is exactly what it should be: a book of writing and art. Long may Maira Kalman live, write, and paint.

The Backyard Bird Chronicles by Amy Tan ... Review+

What a wonderful journal of thoughts and observations by Amy Tan, who also is a fabulous illustrator. The Backyard Bird Chronicles is beautifully written and published (thick paper, suitable for color plates) and $35, which is cheap for a book with this kind of art. (I read a library copy.)

Finally I get this birder thing. Amy Tan chronicles not only the "bird community" in her lush backyard, but her own mind chatter—and she is self-revealing in that way that I'm guessing most people will relate to: all of our judgments and worries, etc. The entries range from informative to funny to sad and even heart-breaking (it is a rough world in the wild, even in the well-tended world of backyard birdfeeders) to inventive (a wonderful "live commentary" of "The Windowsill Wars" for bird food). And I so admire her care for all living creatures—from the birds to the live mealworms she feeds them. She roots for life but has the ability or tolerance to watch death.

I live in NYC, right off Central Park, and for most of my decades here I had dogs (my last girl died a couple of years ago), so I was well acquainted with the human "bird community" in Central Park's woodland area, The Ramble. [If this sounds familiar, it is because the well-publicized horrific racist incident with one of the long-time birders, Christian Cooper, was in the north end of the area.] Historically, the birders are not fond of the dog people who chronically break the leash laws in the Ramble. And the dog people, who are there year round no matter the weather, are not that fond of the birders who tend to travel in massive aggressive herds, moving like a seasonal invasive species oblivious to anything or anyone on the ground who is not a bird. There are obnoxious birder guides who show off by blasting their bird calls through the serenity to impress the people who've paid to go on their tours. In short, there is obnoxious behavior on both sides of this birder/dog people history. But after reading Amy Tan's book, I finally get it: the birds are just like us—complicated, scrappy, territorial, with bullies and submissives, predators and prey. Maybe I'll even take my binoculars there myself now that I'm solo. (N.B. The solo birders are no problem—some became my friends over the years. Christian Cooper was not a herd-group birder, and the woman who falsely accused him was a newbie dog person—Ramble etiquette is, when caught off leash, to say "Sorry" and leash up—no big deal.)

At the beginning of the book, Amy Tan writes about how she was taught to "become the bird" by her drawing instructor, and she does—struggling to understand how they recognize individuals and why they do what they do and if they can change their habits . . . which brings me to:

Some thoughts on energetic and telepathic communication that Amy Tan never mentions:

In my years of watching birders in the Ramble so obsessed with peering through binoculars and camera lenses, I often had a fantasy. Or an idea for a cartoon: what if somehow what they saw were birds staring back at them through tiny binoculars?

The thought amused me and still does, and, often while reading this book, I found myself envisioning this.

Amy Tan is mostly focused on common human senses of sight and sound in her musing about why birds react the way they do—even wondering why they are fine when she's looking at them naked-eyed through her glass doors, but the instant she picks up her binoculars, they take off. She posits that it is because she looks scary.

This brings me to a New York City anecdote:

Our Bodies Are Maps

Our bodies are maps—not of regions but of history. And not only of our own history, but of the history of our ancestors. So when I learn history, I'm learning and feeling it in my body.

I'm reading The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance, the personal research and story of author Rebecca Clarren about her Jewish ancestors and how they came to settle in South Dakota—specifically land that had been stolen from the Lakota, and to this day, still legally belongs to them (the Black Hills), because they refused a monetary settlement from the U.S. government. This is a region where Trump held a rally, and his supporters yelled at the Lakota protestors to "go back to where they came from"—ignorant to the truth that they were standing on Lakota land.

To me, this is beyond the pale.

Did you ever wonder where the expression "beyond the pale" comes from?

The Pale was a region—or more accurately, a reservation or ghetto that Jews were relegated to by the Russian empire.

In the bad old days of a dysfunctional relationship with my late mother, she often yelled at me, "This is beyond the pale!"—her judgment about everything from the way I thought and the things I didn't care about to the way I was in the world. This changed after I banned her from calling me and refused to see her, except when I initiated it. The ban lasted for a year, during which she got some behavioral therapy that taught her not to criticize me; she didn't need to understand why. So she practiced it, and we became best friends.

But just now, reading about the history carried in her and my own DNA—a history relegating us and life itself to a narrow body of land called the Pale, a region outside of which you would be killed, and even within it, you were subject to chronic terrorist attacks, called Pogroms, from the Cossacks when they would butcher, rape, and burn everybody in a town, I understand the fear that must have constricted my mother and that was behind judgments whose deepest wish was to keep me alive.

No wonder that as I read this book, my body feels battered and exhausted.

Review: James by Percival Everett

James is the 22nd book I read by Percival Everett. When I was at book #18, I met the man when he spoke on a panel here in NYC where I live. I'd brought my copy of Erasure for him to sign. I'd chosen carefully—the newest looking of his books on my shelf. I wanted to present him with something pristine.

After the panel discussion, I crept out of the audience, around the circle of panelists' chairs, and, like a teenager with crush, smelling my own sweat, I said, "Mr. Everett, would you sign my book?" He couldn't have been more affable. And as he wrote, I blurted, "I've read 18 of your books." "Oh, so you're the one!" he joked, a line I sensed he used a lot to those of us in what was then a small cult of fans. Undeterred, I further blurted, "When I first discovered your work, I felt like my head exploded."

He smiled kindly and handed me my paperback, fully aware that I was as in love with him as a reader can be from only an author's books, and I didn't know what to do with the feelings.

Every one of Everett's books is different, but having read so many, I feel like all of them have led to James. James is far more accessible than a lot of his other books, and it is perfectly timed to convey his essence to the huge audience he has "suddenly" evoked due to a movie based on Erasure that he had virtually nothing to do with. (I have not seen it because I like the edge in his books, his anger, his uncompromising intellect—even when it is over my head—and his refusal to mitigate any of it with anything that would make his work more accessible, and I've heard that the movie softens all that.)

What is Percival Everett's essence?

For me, it is the thing that made my head explode on first contact: he is absolutely himself. He refuses to fit into any box, under any label designed by someone else. There is loneliness to this kind of a life. A loneliness that can become a choice because at some point you know that nobody—or very few people—will see you as you know yourself to be. (He writes about this in not only Erasure, but in I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Dr. No, God's Country, and many of his short stories.)

In James, he has parsed this out for the masses, using Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn as a launch pad.

Why this book now?

Because it's legal—The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, written in 1884, is now in the public domain. But more importantly, perhaps because the masses are now open to hearing that Black people are and always have been individual people with individual thoughts, ideas, and peculiarities just like all human beings.

This sounds obvious, but in our country it is anything but—proved by the stereotypes that make Black men "dangerous" and all the other notions that weave through our culture.

As in many of Everett's books, James disarms us with humor. There are the fools, the clowns whose cruelty is matched only by their idiocy. As in one of my favorite of Everett's short stories, "The Appropriation of Cultures" (in his anthology Damned If I Do), there are ingenious absurd yet logically-obvious-except-nobody-has-thought- of-them plot twists. There is the unpredictable picaresque journey (I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Dr. No). And there is also an undertow of "yearning to be seen and known." (I wrote about how subversive this is in the book-within-the-book of Erasure; I have no idea if Everett would agree with my take, but it's what I felt.) This is what gives Everett's books a subliminal heartbeat . . . and it hurts—in a good way.

New in this book, although there are aspects of it in other books, is the utter exhaustion of the code-switching Black people have learned by necessity by the time they have social interactions. And, here, that is married to the exhaustion of living in a slave culture of "duplicity, dishonesty or perfidy (195)" where you can't tell who is telling the truth or who might act like an ally but turn out to be the worst kind of enemy. But because of Everett's genius, reading James is never exhausting and always entertaining.

And for me, the newest aspect of this book is a full pulsing catharsis—set up by the ending of his remarkable God's Country in 1994, delivered in an almost mythical form in 2021 in Trees, and finally, in James, experienced through the heart of a man who loves his wife and young daughter, who loves the son who didn't know him as a father, and loves life enough to fight for it.

Oh, my heart!

Review: Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think about Race and Identity by Michele Norris

Our Hidden Conversations is an almost 3 lb., 9.5x7.75-inch, 471-page world of all of us. I didn't believe I could finish it in the space of a library loan, so I posted an early review to Goodreads, which I'm replacing with this one now that I have indeed slurped it down well before its due date.

This is us. This is everybody—all races, genders, the whole mess.

The book is packed with remarkable stories, history, analysis, and real-people quotes. (It's the perfect follow-up to Isabel Wilkerson's The Warmth of Other Suns, which I just reviewed.)

From a section by author Michele Norris:

"I find it deeply ironic that there is such a fierce battle to evade and erase historical teachings about slavery because, in the time of enslavement, there was such an assiduous effort to document and catalog every aspect of that institution, much in the way people now itemize, assess, and insure their valuables. The height, weight, skin color, teeth, hair texture, work habits, and scars that might help identify anyone who dared to flee were documented. The menstrual cycles of enslaved women and their windows of fertility—because producing more enslaved people produced more wealth—were entered like debits and credits in enslavers' ledgers." (178)

Michele Norris's commentary is wise, compassionate, objective, and elucidating, and the effect of all these stories—they came out of Norris's The Race Card Project which invited people to send postcards with 6-word thoughts on race—is to showcase how much we all have in common. Everybody is pained by being judged and put in boxes they don't identify with, asked ignorant questions, insulted by others' lack of understanding that they are even being insulting.

Everybody is in this book, and so that includes plenty of White people who tell their stories of difficulty and deprivation. There are first-person accounts of the struggles we have at other people's assumptions, biases, and projections. Black, White, Native, Arab, Middle Eastern, Asian, mixed-race people and families, adoptees and adopters, gay people, people with disabilities, poor people, White men who are turned down because of being White men. Nobody is left out. And it seems that most of us believe that nobody but similar people with difficulties really understands what we face.

3 Novels I've Loved in 2023

Shepherd is a fairly new book-finding site that is trying to mimic the experience of browsing in a bookstore and running into someone who waxes poetic about a book they can't stop talking about. This book lover tells you in personal detail what they loved about the book and how the book made them feel.

Shepherd invited me to recommend my three favorite books read in 2023. Honestly, I can't choose favorites. But I did choose three books that I love for personal reasons that also inform my own writing. And I got to mention one of my novels that I think embodies a lot about the books I recommend.

Here's the link: Shepherd

Review: Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America by Heather Cox Richardson

In Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America, historian and "people's teacher" (via her social media and newsletters) Heather Cox Richardson has created a sweeping connect-the-dots history of how we got to where we are now. Where we are now—grappling between remaining a democracy or becoming an authoritarian country—has long roots, and in Parts 1 and 2, she starts at the beginning of American history and follows those roots into global history (mostly chronologically, but when she backtracks—specifically tracing the Nazi rally in Charlottesville, VA, back to its historical beginning—it is organic and easy to follow). Once we advance into the events of the last few years, people who follow the news will already be fully informed, but this is a book that will stand as a valuable history for future readers, so it is great to have all this documented in story form.

I cannot possibly reduce this work (or even retain as much as I'd like—this is a book to read multiple times), so suffice it to say: it is readable, fast, understandable, and rather than throwing in absolutely every detail as a lot of historians do, she opts to tell a specific American story efficiently: the story of American democracy—a belief that all people should have equal rights and have a government by their consent.

Because I'm interested in why people are so vulnerable to manipulation, power-greediness, and a herd-like compulsion to move with others even when doing so makes no sense and undermines democracy, I was particularly struck the very first time I read about a nonsense statement that split people into warring cultures:

[In 1971] Phyllis Schlafly said: "Women's lib is a total assault on the role of the American woman as wife and mother and on the family as the basic unit of society. Women's libbers are trying to make wives and mothers unhappy with their career. . . ." (pg. # NA)

This kind of statement, assuming that if anybody gets something (or said another way, if everybody gets equal rights), somebody else must lose something, is key to Movement Conservatism (creating rifts between oneself and others who are deemed "bad") that Cox traces back to 1937. And it is key to the intentional attempt to destroy civil society, establish chaos—which most people will do anything to stop—and thereby lay the foundation for people's desire for a "strong man" to make it stop, evoking authoritarianism and extinguishing democracy.

You could plug into this kind of "this causes that hurt/loss" statement any number of things: true history that includes our racist roots; the right to decide what we do with our bodies; climate change causes; etc. This critical false equivalence (lie), I believe, can only be combatted if people decide to think—use common sense—rather than react in fear of chaos. And common sense is a real possibility: In Part 3 of this book, Cox writes about how powerful common sense was in moving us to independence: Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense rejected the idea that any man could be born to rule others and called "ridiculous" the notion that an island should rule a continent. "Paine's spark set to flame more than a decade of accumulating timber," writes Cox, leading to declarations of independence. The real revolution Americans experienced was in thinking rather than fighting.

Here's my common sense: It is absolute nonsense that women having equal pay and rights could hurt marriages. How? Women who want to be homemakers will not be forced to work. Teaching true history will not hurt white people; I and most white people I know will grapple with questions about our own commitment to what's right and would we have been strong enough to act as an abolitionist? I don't know anybody who identifies with slave-holders. If somebody does not want to accept equality and history of inequality, they don't have to, but true history can still be taught in schools. If somebody doesn't support the right to body autonomy for themselves, they don't have to; nobody will ever force them to have an abortion and if they don't want to make their own medical decisions, they can find some authority to hand responsibility over to. If somebody does not accept that our actions are destroying the earth, they are free to believe that. Yes, pollution regulation will change lives, but I wager that anybody who wants to pollute their home will still be able to do so. Nobody will have to love people they don't love if others have the right to love who they love. You don't have to believe what you don't believe.

There is no loss for anybody if more people do better by telling the truth and having equal rights. The whole notion of consequent loss is nuts! Read More

Sun House by David James Duncan

Sublime. That's the fastest way to describe this writing, this story, this world birthed by David James Duncan.

For almost 800 pages I've been swimming in the Ocean of Sublime—an ocean you can just as easily drown in as float. I'll get to that in a moment.

Second and third thoughts: How the f**k did he write this (let alone get it published) and how on earth can I convey what this is to people who may consider it a foreign language as well as the few humans who live for this stuff?

I don't know the answers to either of those questions. In addition, I don't know who besides me would be so drawn into this book.

I can tell you that there is a mythically romantic tone throughout and there are two main characters who start the book in separate stories in Portland, OR, and Seattle, WA (location is as much a character as any person): a boy-man, Jamey, and a girl-woman, Risa. I can tell you that they are idiosyncratic, independent thinkers who feel even more deeply than they think. I can tell you that Jamey is a people-loving, irrepressible clown with a father and a dog you fall in love with. I can tell you that Risa falls in love with Sanskrit sounds and language and Vedic sages and the whole world they birth and then lives with Grady, the funniest horniest philosophy student ever written, and then with Julian, a good-looking prick who is threatened by her love of "Skrit" and the inner journey. And I can tell you that the first-person narrator feels like a person-god, who I don't believe in, but he has such a great sense of humor that I more-than-willingly suspended my disbelief.

There are plenty of other characters who appear first in their own chapters. For instance: a mountain climber and a singer who love, have a kid, then don't love; an ex-Jesuit priest and his twin brother, a street nonpriest-sadhu who gathers a flock anyway, whose epistolary history of the Catholic Church's persecution of the Beguines mesmerized me (if Herman Melville had been this joyfully light-hearted and in love with his history of whales, he could have gotten away with it).

And in a symmetry that makes subliminal sense, these people finally begin to converge in the mountains of Montana exactly halfway through this epic in an "Eastern Western"—meaning "When East [spiritual traditions] touches West [the region of the USA], the central struggle is against cosmic illusion . . . (p. # NA)" And this is when the storytelling starts to crank up, so if you get bogged down in the first 400 pages, but are liking it, stay with it . . . particularly because, very soon after the convergence begins, the god-person narrator actually explains the unorthodox structure of this massive book, and hearing it can make you sparkle, as well as spiritually roar in the backtracked scene when Risa and Jamey finally start their journey together.

I found out the hard way that I needed to take breaks. Everybody speaks within a style of cascading thoughts, although it's slightly different for each character. (Think of Shakespeare's iambic pentameter or Aaron Sorkin's smart-smart-smart speed-demon, fact-laden intellectual torrents.) When I tried to read too many chapters without a rest, the spiritual stream-of-consciousness became tedious. So subsequently I took many breaks, and when I returned, I was open to the Voice behind the voice and ate it up; I realized taking breaks also evoked contemplation about what I'd read, and it was in contemplation that the heavy text got light and worked on me. Also, there are enough heavenly narrative actions and descriptions (see sample below) to break up the thought tirades.

If your life is completely focused on the surface of here and now—plot-plot-plot—and you are uninterested in awareness, enlightenment, or any kind of transcendent journey, let alone the power of the sounds of language beyond its literal meaning, you will not be interested in this book. In fact, you may feel like the distracted bar crowd who "don't get" what makes Risa, Jamey, and readers like me spiritually roar during their ecstatic convergence over a story of Gandhi's death.

But if you are a person who longs for Oneness, who is compelled by the debate between the counter-evolutionary force of ego vs. the evolutionary force of enlightenment (to embody "free nothingness at Ocean's [consciousness, All That Is] service" (p. # N/A)," if you're convinced that enlightening yourself is the only real work to be done in this life, if you pace yourself, eagerly surrendering, even to a language that sometimes strikes your poor undereducated head as chicken-scrawled squawks and the poetry of a holy fool (think Paul Beatty's screamingly hilarious The Sellout, only substitute the literary classics, mountain climbing, and Eastern philosophies for research psychology and The Little Rascals), you may end up in a blindingly brilliant roofless Sun House of indefinable dimensions—happier and more heartbroken than you imagined possible. Read More

The Postcard by Anne Berest

To say I was possessed by The Postcard and its author, Anne Berest, is not an exaggeration. I was possessed, obsessed, and grateful. It is 475 pages that I only put down when my eyes felt swollen: a novelized true story of Berest's family's experience when Nazis invaded and occupied France and Berest's investigation of that many years later. It is only called a novel because Berest wanted to write it as a nonlinear novel with dialogue and full characters, changing names of collaborators so that their descendants would not be persecuted, but this is a copiously researched investigation of what happened, who did what, and how Berest came to be a secularized Jew—when she began her investigation, she didn't identify as Jewish, look Jewish, had never followed the religion or been in a synagogue and had no experience in the culture.

This mystery, quest, hunt—told with all the dramatic tension of such stories—quickly became one of the most deeply personal experiences I've had. Read More

Review & Cover Complaint: "Leg--The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It" by Greg Marshall

Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It (Abrams, June 2023) by Greg Marshall

What an explosively entertaining memoir! Raucous, ribald, and really well written. I've been reading a lot of history full of pain and statistics, so Greg Marshall's memoir was a welcome and uplifting relief.

One complaint: the cover art of a perfectly proportioned naked man bugged the hell out of me. It was chosen by Lithub for a list of best covers for June 2023, but I would love to hear from others who have actually read the book—a book whose title is about a badly distorted leg and a lifetime of experiences that are affected by that.

(By the way, I felt the same ire about the original hardback cover of Susan Jane Gilman's equally hilarious novel The Ice Cream Queen of Orchard Street—a pair of elegant ankles—when a major character feature is the protagonist's damaged leg/ankle. This cover was changed (because of the outcry?) on the paperback and the hardcover is no longer listed on Hachette's website.)

Leg's cover design, as noted by Lithub, is striking, but imagine how much more striking it would be if it accurately portrayed what's inside this fabulous memoir about having Greg's leg and body's condition willfully kept from him, being gay, and being part of a family that made all that, as well as cancer, dying, etc. hilarious!

Not only is the perfectly proportioned man given in front view, but he's on the back cover in rearview, and as if to put a button on the lie, there is a gorgeous well-muscled leg on the spine.

I protest this design and, having worked as a managing editor of a magazine, can imagine the endless meetings discussing it: "We can't show a real crippled body and leg—people won't buy the book; they'll be turned off or shocked. Focus groups have shown people may say they are accepting of differently abled people, but when it comes to spending money, after seeing an image of one . . . !"

Have the balls (yes, big balls also make several appearances) to match the cover to the daring, irreverent, explicit interior. Trust the reading public to be intrigued and want to read it even more. (If somebody is turned off by an accurate cover, they would probably not be a happy audience for this fabulously original work.) Because I liked this book so much, every time I picked it up, those pictures felt like an insult, and I can only imagine how a person with a disability would feel.

Images matter. If we don't see it/them/ourselves in artistic representations, it is foreign—even to the people who live with being "different."